Introduction

This is the sixth installment in a series of blog posts about Support Vector Machines. If you have not read the first five blog posts, I highly recommend you go back and read those before continuing on to this blog post.

Last time we looked at kernels and the kernel trick, which allowed us to use SVMs to classify data that is not linearly separable.

In this blog post we will be focusing once again on how we train SVMs. In the third blog post I introduced Quadratic Programming and we used the CVXOPT QP solver in Python to train our SVM.

In this blog post I will be describing in detail a superior algorithm specifically designed for training Support Vector Machines called Sequential Minimal Optimization (SMO).

Sequential Minimal Optimization is a modified version of an optimization algorithm called coordinate ascent. In SMO, we solve the optimization problem posed by the SVM dual iteratively by solving the smallest possible optimization subproblem at every step.

Why Sequential Minimal Optimization?

Why do we even need SMO? We were already training our SVM without it, after all.

It is true that we can train SVMs using Quadratic Programming solvers such as CVXOPT. As a matter of fact, until SMO’s discovery/invention by John Platt in 1998, QP solvers were how SVMs were trained. There are many issues with QP solvers, though.

First of all, QP solvers are notoriously tricky to implement. There are many numerical precision issues and things like that to deal with. SMO is quite straightforward to implement. We will be implementing the algorithm ourselves from scratch.

Also, the techniques that QP solvers use to actually train SVMs involve keeping very large matrices in memory, and performing computationally costly operations with them. In the toy examples we looked at, you likely wouldn’t have run into any issues, but in a real scenario you could very easily hit a wall with large data sets where QP solvers are simply too inefficient to get the job done. SMO, on the other hand, does not require any of these expensive matrix operations whatsoever.

Coordinate Ascent

Coordinate ascent is an algorithm for maximizing objective functions.

The algorithm goes like this:

- Start with an initial guess at what the variables should be.

- Pick one decision variable.

- Find the partial derivative of the objective function with respect to that variable.

- If the partial derivative with respect to that variable is 0, pick another variable. If the partial derivative with respect to all variables is 0, you’ve found the maximum.

- Step that variable in the direction of that partial derivative, keeping the other decision variables constant.

- Repeat from step 2 until you’ve found the maximum.

Let’s take a look at one of the examples we saw in the second blog post:

This is a minimization problem. Coordinate ascent is for maximizing objective functions.

I’d like to change this minimization problem into an maximization problem so that, if we successfully perform coordinate ascent, we will get the same answer we did in the second blog post. To do this we just need to negate the objective function.

Alternatively, we could modify the algorithm slightly to step the decision variable in the opposite direction of the partial derivative. This is called coordinate descent, and it would minimize our objective. For the sake of relating this to SMO, we will stick with coordinate ascent.

Now, we start by picking an initial guess at our decision variables ( and

). Let’s set them both equal to

.

Let’s start by optimizing .

We find the partial derivative of our objective with respect to :

We plug in our current value of , which is 0. We get

.

Now we need to step our current value of in the direction of the partial derivative. The partial derivative is positive, so we know we’re going to move

in the positive direction. Usually we pick a “learning rate”, some fixed value that we multiply our derivative by to get our final step amount. Let’s pick a learning rate of

.

So we increase by 4. Plugging our new

back into the partial derivative equation gives us

. Our partial derivative is

! That means that we’ve optimized our objective function for

.

Now we repeat the process with and get an optimal value of

. This is a maximum of our function.

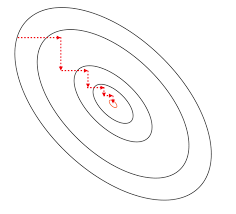

Graphically, coordinate ascent looks like this:

The ellipses are the contour lines of our function. The red lines represent the steps we take in the direction of and

. As you can see, we make axis-aligned movements towards the maximum.

Sequential Minimal Optimization

So, can we use coordinate ascent to optimize the SVM dual?

Recall that the SVM dual is:

subject to:

Unfortunately, we can’t. The reason we can’t is the linearity constraint:

This means that all of the Lagrange multipliers lie on a line. Each is a function of all of the other

s. If we knew all but one of the

s, we could solve for the other deterministically.

To get around this, SMO uses a modified version of coordinate ascent where we solve for two Lagrange multipliers at a time.

Derivation

This section is a full derivation of the solution for one iteration of SMO’s modified version of coordinate ascent. I could not find the full derivation anywhere online so I feel compelled to post it in its entirety, step by step. The original paper has a derivation, but it skips over a lot.

If you do not care about the derivation you can skip this section. If you see any issues in my derivation please let me know.

Our goal is to optimize the SVM dual by solving for two Lagrange multipliers at a time.

Looking at the linearity constraint:

We can rewrite it to be in terms of and

, the two Lagrange multipliers chosen for optimization:

The term on the right-hand side is just some fixed constant that we can calculate. We will call this constant :

We can now solve this equation for :

Since is either

or

we know that the reciprocal of

is just

:

Distributing the gives us:

Now, I would also like to make a substitution in this equation using this equality:

Plugging this back into the equation for we get:

Now we can rewrite the dual in terms of and

.

This looks very complicated, but all I have done is separate the terms in the summation that include or

out of the original equation.

Now, we can reformulate this equation into being in terms of only by substituting

in:

Now, I will introduce another variable to help simplify this equation:

Plugging in and rearranging terms a bit we get:

Now we have the dual equation in terms of only two Lagrange multipliers. This is still a Quadratic Program. We could plug this into a QP solver and it would still be much faster than before overall because we only have two decision variables.

We can do even better though, and solve for analytically, thus avoiding the need for a QP solver altogether.

To analytically solve for we differentiate with respect to

and set it equal to 0.

Let’s differentiate it term by term:

First Term:

We differentiate this with the chain rule and get:

Second Term:

We use the power rule:

Third Term:

Here we just apply the constant rule and get:

Fourth Term:

First, we distribute the :

Next, we distribute the :

Therefore:

But, recall that :

Because must be either

or

,

is always just

:

Fifth Term:

This is a straightforward application of the constant rule:

Sixth Term:

First, we distribute the negative:

Then apply the constant rule:

Seventh Term:

This is obvious:

Eighth Term:

The eighth term is a constant that does not include so it goes away when we differentiate.

At long last putting the terms together into one equation and setting that equation equal to zero gives us:

Now, we need to solve for to find our optimal solution. It is a lot of algebra. I will do it in small steps explaining each step as I go.

First, we can move over to the other side of the equation:

Now we can factor a out of the terms of the right side of the equation, and move it over to the other side of the equation:

Wherever there is parenthesis on the left side of the equation we can distribute:

Since and

must be either

or

,

, and those terms disappear. This will come up a lot during this derivation.

Combining like terms:

We can factor out the and

from the leftmost terms and move them over to the other side of the equation:

We can factor out the on the left side:

At this point we need to take another look at the equation for to make more progress:

Solving for gives us:

We don’t know what and

are supposed to be yet for the current iteration, but we do know what they were last iteration. Because of the linear equality constraint, it must always be true that:

Where the starred variables are the values found in the previous iteration.

Plugging this equation in for we get:

Distributing some of the parenthetical terms out on the right side of the equation gives us:

Now, to make further progress we must revisit the equation we had for :

Defining a new variable, which is the guess given the current parameters of our

th training example in terms of the Lagrange multipliers:

We can solve in terms of

:

Once again this is in terms of the values from the previous iteration (our current parameters).

Plugging this equation for into our equality we can make more progress:

The s cancel out:

We can distribute the . Anywhere where there would be a

can be replaced with an

and anywhere where we have

s multiplying each other we can just get rid of it because

Now we have some terms that cancel out:

We can group all of the terms containing together:

And factor out a :

Now we can factor out a from the other terms on the right side:

Notice how became

and

became

because

and

must be either

or

.

Now, I will define another variable:

And substitute into the equation:

Now we divide both sides by :

The original paper defines another variable:

which is the “error” in the th training example.

Rewriting our equation in terms of gives us:

Which is the equation found in the paper.

Keeping The Solution Feasible

There is one more step,

This is the analytical solution for , but it does not take into account the inequality constraints:

All we need to do to obey these constraints is to clip our value so that it is within these constraints.

For example, we know from the linearity constraint:

Solving this equation for and

we get:

We know that all of the s must either be

or

, whether they are the same or different will tell us the signs involved in this equation.

There are two possibilities:

Let’s first take a look at the case where :

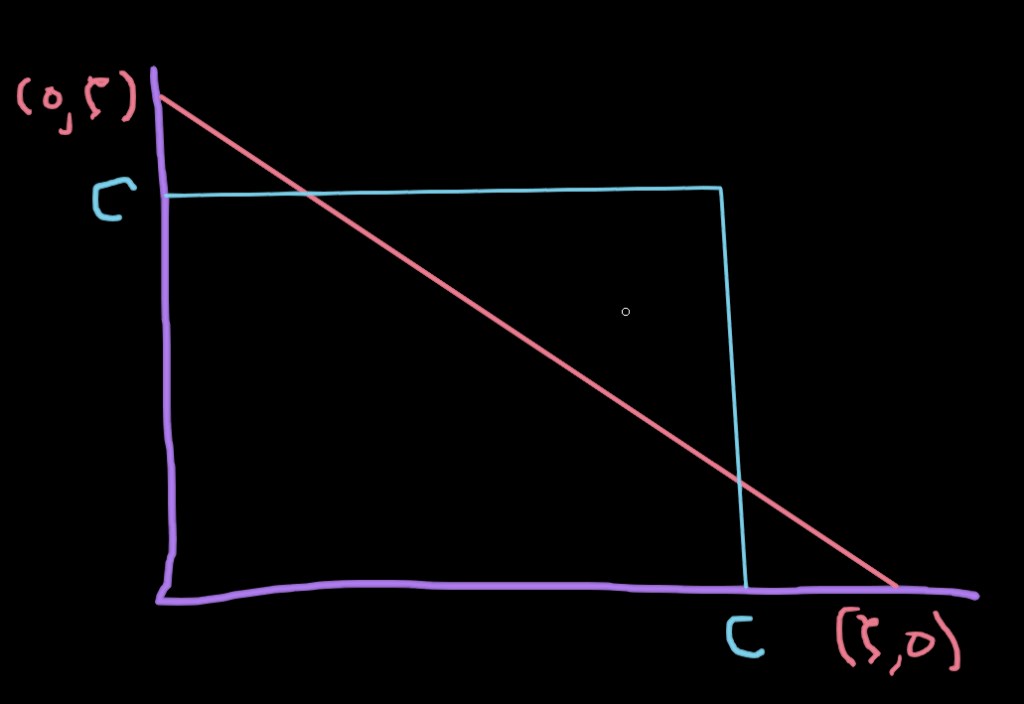

We can plot this line to help gain some intuition about how we need to clip to satisfy the inequality constraints:

A solution which satisfies the linearity constraint must lie on the diagonal line:

As you can see when the line crosses the axis at

. This is gotten from the equation for the line:

When = 0, the equation becomes:

The same is true of the other end of the line segment when .

Not only must our solution lie on this line, but it must also lie within a box because of the inequality constraints: :

If we let span its whole range

, then

must be between these two bounds,

and

:

We can define the bounds like this:

Plugging back in the equation for to get these in terms of

and

we get:

If the labels are not equal to each other: the equation for the line becomes

and the picture looks slightly different:

Now, the bounds look like this:

Again, writing these bounds in terms of and

:

That’s it. We can now solve for two Lagrange multipliers at a time in the dual problem, keeping the solution feasible at every step.

Conclusion

To recap the algorithm it goes like this:

- Select two Lagrange multipliers,

and

to optimize.

- Solve for

using the equation

- Clip this solution for

to be within the feasible region given by the bounds

and

.

- Repeat until convergence.

There is a whole other component of the algorithm that the paper goes into which is heuristics for choosing which Lagrange multipliers to optimize, but we can just select them at random and it may still converge. I will put that off until later for now, and jump into the simplest possible implementation of SMO.

Thank you for reading!

Leave a comment